Moral Turpitude Gambling

Posted By admin On 08/04/22- Moral Turpitude Gambling Laws

- Moral Turpitude Gambling Definition

- Moral Turpitude Gambling Meaning

- Moral Turpitude Gambling Law

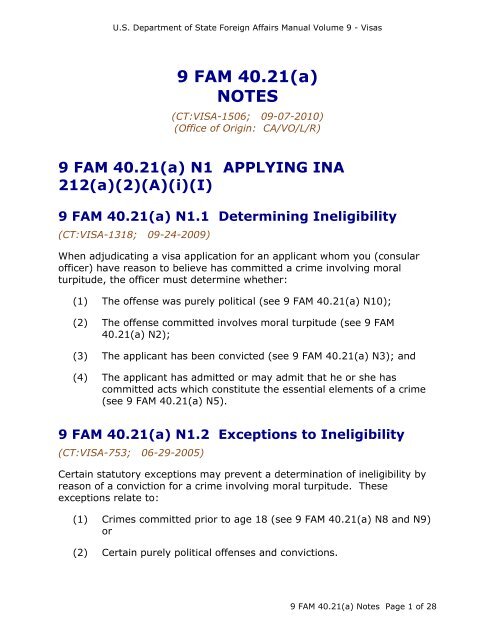

INA § 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(I) Conviction/sufficient admission of a crime involving moral turpitude (CIMT ). BUT Juvenile offense exception BUT petty offense exception INA § 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(II) ANY controlled substance offense conviction or violation of a law relating to a controlled substance (no exceptions). (U) Evaluating Moral Turpitude Based Upon Statutory Definition of Offense and U.S. Standards: To render an alien ineligible under INA 212(a)(2)(A)(i)(I), the conviction or admission must be for a statutory offense which involves moral turpitude. The presence of moral turpitude is determined by the nature of the statutory offense for which the.

In re Calaway , 20 Cal.3d 165

In re MARTIN C. CALAWAY on Disbarment

(Opinion by The Court.) [20 Cal.3d 166]

COUNSEL

Donald B. Caffray for Petitioner.

Herbert M. Rosenthal for Respondent.

OPINION

THE COURT.

This is a proceeding to review a recommendation of the Disciplinary Board of the State Bar of California that petitioner be disbarred. Petitioner, who was admitted to the practice of law in 1956, was convicted in federal district court of violating 18 United States Code section 1955 (conducting, financing, managing, supervising, directing or owning an illegal gambling business) and 18 United States Code section 371 (conspiring to violate § 1955). The conviction was affirmed on appeal and is now final. (Although petitioner has applied for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court, based on alleged incompetence of trial counsel, the pendency of this petition does not affect the finality of his conviction.) On May 1, 1975, we referred the matter of petitioner's conviction to the State Bar for hearing, report, and recommendation on the question whether the facts and circumstances surrounding the commission of the offenses involved moral turpitude or other misconduct [20 Cal.3d 168] warranting disciplinary action. (See Bus. & Prof. Code, §§ 6101, 6102; Cal. Rules of Court, rule 951(c), (d).)

A local administrative committee, following a hearing, found that petitioner 'was actively involved in the criminal conspiracy of which he was convicted, such activity including financing, managing, counselling, and supervising an illegal gambling operation.' The committee further found that petitioner 'willfully and knowingly' engaged in the conspiracy and illegal gambling operation; that he made his legal services available to further the conspiracy and to counsel and protect his coconspirators; that he assisted in locating customers for the game and ultimately received some of the proceeds thereof; and that he improperly used conservatorship funds to finance the operation. The committee concluded that the offenses of which petitioner was convicted involved conscious and willful acts of moral turpitude on petitioner's part, and recommended that he be disbarred.

The disciplinary board voted to approve and adopt substantially all of the committee's findings and also specifically found that the facts and circumstances surrounding petitioner's offenses involved moral turpitude. The board, by a vote of nine to four, recommended that petitioner be disbarred. (The dissenters would have recommended less severe punishment.) [1a] Petitioner now contends that the record fails to support the findings of fact, that the offenses at issue did not involve moral turpitude, and that the recommended discipline is excessive.

The record discloses that petitioner and his coconspirators were involved with an unlawful gambling operation in the San Fernando Valley. Although petitioner denied (and continues to deny) his knowledge of, or participation in, the illegal conspiracy, the federal court convicted him of both the substantive offense of illegal gambling as well as conspiring to commit that offense. A review of the record in the federal case discloses sufficient evidence from which the following facts reasonably may be inferred: Petitioner participated in the preliminary discussions between the coconspirators which ultimately led to the formation of the unlawful gambling operation. Among other things, the parties discussed during these meetings the financial contributions which each would make, and their respective shares of the proceeds. Petitioner was to contribute $20,000 as his share, consisting of $10,000 in cash and $10,000 in legal services; in return for his contribution, petitioner would receive from 20 to 25 percent of the 'take.' [20 Cal.3d 169]

Petitioner, with knowledge of coconspirator John Vaccaro's status as a professional gambler and his intent to set up an unlawful gambling operation, loaned $7,500 to him, at least $2,500 of which was actually used to fund the game. Petitioner ultimately invested $5,000 and received in return some of the proceeds from the illegal gambling. Petitioner gave nonlegal advice to the coconspirators regarding the practical aspects of their illicit endeavors, including the obtaining of gambling equipment, chips, and customers to frequent the new establishment, and the purchase of 'sanction' or protection from the police. Petitioner also gave legal advice to the coconspirators regarding the illegal nature of the proposed operation and the necessity of concealing its activities.

The dice and card games operated by petitioner's coconspirators were 'rigged' to cheat the customers and increase 'house' profits. From petitioner's close association with coconspirator Vaccaro, and his financial interest in the operation, it may reasonably be inferred that petitioner was aware that such cheating of customers occurred.

In addition to the foregoing, the record indicates that the $7,500 loan from petitioner to Vaccaro came from funds held by petitioner as conservator of the estate of an 86-year-old incompetent; that these funds were disbursed without the knowledge or approval either of the conservatee or of the court with jurisdiction over his affairs; that the loan was not disclosed by petitioner's subsequent accountings; and that the loan was not fully repaid until after the federal prosecution had commenced.

Petitioner contends that the offenses of which he was convicted did not involve moral turpitude. [2] Although petitioner has the burden of showing that the board's finding of moral turpitude is not supported by the evidence, the question of moral turpitude itself is one of law, ultimately to be decided by this court. (In re Hurwitz (1976) 17 Cal.3d 562, 567 [131 Cal.Rptr. 402, 551 P.2d 1234].) In this regard, it is our duty to examine independently the record, reweigh the evidence and pass on its sufficiency. (Ibid.)

[1b] Our independent review of the record convinces us that petitioner committed acts involving moral turpitude. [3] As we have stated on many occasions, moral turpitude has been defined as 'an act of baseness, vileness or depravity in the private and social duties which a man owes to his fellowmen, or to society in general, contrary to the [20 Cal.3d 170] accepted and customary rule of right and duty between man and man.' (In re Fahey (1973) 8 Cal.3d 842, 849 [106 Cal.Rptr. 313, 505 P.2d 1369, 63 A.L.R.3d 465], quoting from an earlier case.) ''The concept of moral turpitude depends upon the state of public morals, and may vary according to the community or the times,' [citation] as well as on the degree of public harm produced by the act in question.' [Citation.] The paramount purpose of the 'moral turpitude' standard is not to punish practitioners but to protect the public, the courts and the profession against unsuitable practitioners. [Citations.]' (Ibid.)

[1c] In the present case, we may reasonably infer from the record that petitioner was deeply involved in an illegal gambling conspiracy which had as its purpose the acquisition of profits by cheating its customers. Petitioner disputes the premise that illegal gambling itself involves moral turpitude. He argues that '[g]ambling is a crime in California because of a statute, and not because of some fundamental evil about it that makes it a crime everywhere.' To the contrary, petitioner overlooks the fact that he has been convicted of committing, and conspiring to commit, a federal offense aimed at curtailing syndicated gambling: 'The intent of ... section 1955 [of title 18 U.S.C.] ... is not to bring all illegal gambling activity within the control of the Federal Government, but to deal only with illegal gambling activities of major proportions. ... It is intended to reach only those persons who prey systematically upon our citizens and whose syndicated operations are so continuous and so substantial as to be of national concern ....' (Italics added, United States v. Sacco (9th Cir. 1974) 491 F.2d 995, 1009 [conc. opn. by Hufstedler, J. quoting from a legislative report].) Petitioner's attempt to minimize the seriousness of his conduct fails when the foregoing congressional purpose is considered.

Petitioner points out that he was not found to have participated, personally, in any actual cheating at gambling. Nonetheless, he conspired with other persons who performed such acts, and the record supports a finding that petitioner knew of the cheating activities and encouraged such acts by his own participation, advice, and financial support. We conclude that there is ample evidence to sustain the board's finding that petitioner's acts involved moral turpitude.

Petitioner next contends that the recommended disbarment is excessive punishment for his offenses. [4] While it is our ultimate responsibility to determine the degree of discipline to be imposed, the board's recommendation is given great weight and petitioner has the burden of [20 Cal.3d 171] demonstrating that the recommendation is erroneous or unlawful. (In re Duggan (1976) 17 Cal.3d 416, 423 [130 Cal.Rptr. 715, 551 P.2d 19].) [1d] Our independent examination of the record discloses that petitioner committed acts involving moral turpitude and dishonesty and that the protection of the courts and the integrity of the legal profession require that he be disbarred. The record contains no evidence of petitioner's rehabilitation or remorse; he continues to dispute the seriousness of the offenses of which he was convicted. (See In re Hurwitz, supra, 17 Cal.3d 562, 568.) In addition, as the local committee found, petitioner 'improperly and unlawfully utilized conservatorship funds for the financing of [the] conspiracy,' conduct which by itself would warrant severe punishment. (See Sturr v. State Bar (1959) 52 Cal.2d 125, 134 [338 P.2d 897]; Clark v. State Bar (1952) 39 Cal.2d 161, 166-174 [246 P.2d 1]; Laney v. State Bar (1936) 7 Cal.2d 419, 422-423 [60 P.2d 845].)

It is ordered that petitioner be disbarred from the practice of law in this state and that his name be stricken from the roll of attorneys. It is further ordered that petitioner comply with rule 955 of the California Rules of Court and that he perform the acts specified in subdivisions (a) and (c) of that rule within 30 and 40 days, respectively, after the effective date of this opinion. This order is effective 30 days after the filing of this opinion.

Opinion Information

| Date: | Citation: | Category: | Status: |

| Wed, 11/16/1977 | 20 Cal.3d 165 | Review - Criminal Appeal | Opinion issued |

| 1 | MARTIN C. CALAWAY(Petitioner) |

| Disposition | |

| Nov 16 1977 | Guilty |

Moral Turpitude Gambling Laws

The following types of businesses are ineligible:

(a) Non-profit businesses (for-profit subsidiaries are eligible);

(b) Financial businesses primarily engaged in the business of lending, such as banks, finance companies, and factors (pawn shops, although engaged in lending, may qualify in some circumstances);

(c) Passive businesses owned by developers and landlords that do not actively use or occupy the assets acquired or improved with the loan proceeds (except Eligible Passive Companies under § 120.111);

(d) Life insurance companies;

(e) Businesses located in a foreign country (businesses in the U.S. owned by aliens may qualify);

(f) Pyramid sale distribution plans;

(g) Businesses deriving more than one-third of gross annual revenue from legal gambling activities;

(h) Businesses engaged in any illegal activity;

(i) Private clubs and businesses which limit the number of memberships for reasons other than capacity;

(j) Government-owned entities (except for businesses owned or controlled by a Native American tribe);

(k) Businesses principally engaged in teaching, instructing, counseling or indoctrinating religion or religious beliefs, whether in a religious or secular setting;

Moral Turpitude Gambling Definition

(l) [Reserved]

(m) Loan packagers earning more than one third of their gross annual revenue from packaging SBA loans;

(n) Businesses with an Associate who is incarcerated, on probation, on parole, or has been indicted for a felony or a crime of moral turpitude;

(o) Businesses in which the Lender or CDC, or any of its Associates owns an equity interest;

(p) Businesses which:

(1) Present live performances of a prurient sexual nature; or

Moral Turpitude Gambling Meaning

(2) Derive directly or indirectly more than de minimis gross revenue through the sale of products or services, or the presentation of any depictions or displays, of a prurient sexual nature;

(q) Unless waived by SBA for good cause, businesses that have previously defaulted on a Federal loan or Federally assisted financing, resulting in the Federal government or any of its agencies or Departments sustaining a loss in any of its programs, and businesses owned or controlled by an applicant or any of its Associates which previously owned, operated, or controlled a business which defaulted on a Federal loan (or guaranteed a loan which was defaulted) and caused the Federal government or any of its agencies or Departments to sustain a loss in any of its programs. For purposes of this section, a compromise agreement shall also be considered a loss;

(r) Businesses primarily engaged in political or lobbying activities; and

Moral Turpitude Gambling Law

(s) Speculative businesses (such as oil wildcatting).